In our previous analysis of the S&P 500, we indicated that we expected that stock prices might fall in the very near term in response to both profit-taking and the arrival of a new negative noise event associated with the possibility of a partial federal government shutdown in October 2013.

Sure enough, we can say we saw it coming! We'll squeeze just a little bit more information into the current version before we officially revise it to move past the third quarter of 2013 to show how these things have played out:

The profit-taking is pretty easy to understand, as the stock market enjoyed a run up in prices through much of September 2013 in anticipation that the Fed would not cut back on its current quantitative easing programs. But what about the possibility of a new negative noise event?

That's tougher to tell. Here, we're going to start our analysis today by looking at a bit of data being advanced by at least one uncritical left-wing economist that markets believe that the United States is at a sharply increasing risk of defaulting on its national debt.

Here's what the WSJ article he cites says:

President Barack Obama repeated Thursday that he won't negotiate on the debt ceiling and won't sign any bill that defunds or delays the health-care law. He lashed out at Republicans for what he said were moves endangering the full faith and credit of the country. "You don't mess with that," he said in a speech in Largo, Md.

The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that if the debt ceiling isn't raised, the government will be unable to pay all its obligations sometime in late October.

Investors appear to be eyeing the possibility that the issue won't be resolved, judging by the sixfold increase in the past week—to its highest level since 2011—of the annual cost of derivatives some investors use to hedge against the risk the U.S. will default on its debt.

The WSJ's chart shows how the value of the investment derivatives tied to the risk of a U.S. government debt default have changed since July 2013. But this bit of information is why we describe the left-wing economist as being uncritical, because he is taking it at face value without any apparent understanding of what it is really communicating.

Once upon a time, these kind of credit derivatives, or as they are more commonly known, Credit Default Swaps (CDS), were used by investors to hedge against the risk that an entity, say a firm or a sovereign nation, would default on its debt.

Back in 2011, they were very successful in communicating the risk that a number of European nations were increasingly at risk of defaulting on their debts. So much so that the people who run the European Union scapegoated the trading of credit derivatives for the problems of its failing nations and took steps to effectively ban them by starving them of the liquidity they would need to function as a tool that clearly communicates the risk of default.

This is significant because, as you'll note on the WSJ's chart, that risk is denominated in Euros, not U.S. dollars.

As a result of the EU's actions, credit default swaps are no longer capable of communicating the real risk of whether a nation might default on their debt. Reuters explains:

"Sovereign CDS volumes and liquidity are down massively," said Michael Hampden-Turner, credit strategist at Citigroup. "Part of that is because investors are more optimistic about risk generally, but the EU ban has also hurt liquidity."

"The market tends to be fairly one-way round, leaving it vulnerable to gapping spreads when there is activity. Dealers are not prepared to run big positions as there is nowhere to lay the risk off, which makes it worse. Every quarter volumes slide and CDS becomes less liquid, and that looks set to continue."

[...]

This is a marked change from the pre-ban era, when CDS trading would pick up when a sovereign became more stressed and it was viewed as an important pricing point.

So, if these kinds of credit derivatives are no longer effective communicators of the degree of risk that a nation might potentially default on its debt, what is? Reuters answers:

"People pricing sovereign risk now look at the bonds, so why would you look at the CDS if bonds are where the information lies? Back in the day it was the other way around, with CDS levels being the crucial signal - it's a fundamental change," said Paul McNamara, investment director at GAM.

So, let's look at the yields of U.S. government-issued bonds. Here, if the risk of the U.S. government really defaulting upon its debt had really increased, we would see a spike in bond yields - the interest rates that the U.S. government pays to its lenders. Our first chart shows the yield for the benchmark 10-Year U.S. Treasury for the past year through 27 September 2013:

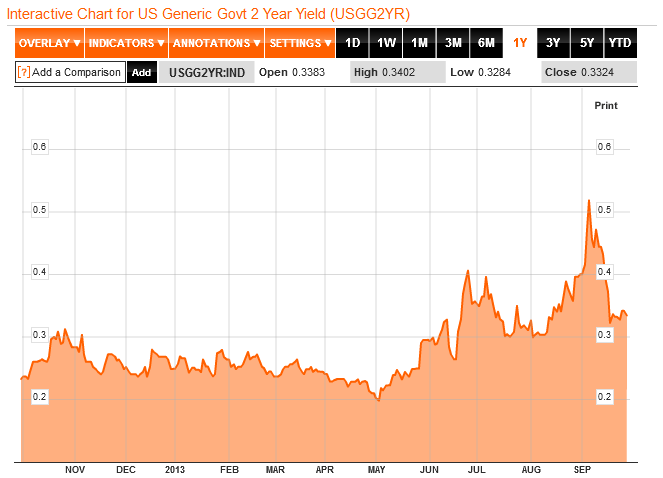

Let's next look at a shorter term bond - the 2-Year U.S. Treasury, which might show a more pronounced response to the near term risk of a U.S. default:

It doesn't do us much good to look at shorter-term U.S. Treasuries, because the Federal Reserve's Quantitative Easing (QE) program has pushed their yields down to near-zero levels. This outcome is specifically the result of what we describe as QE 4.0, which is the portion of the Fed's current QE programs that buys up U.S. Treasuries. QE 4.0 was announced back on 12 December 2012 to offset the imminent risk of a sharp contraction in the U.S. economy resulting from President Obama's desired tax hikes going into effect in 2013, and it has largely succeeded in keeping the U.S. economy out of a full-fledged recession.

In both these charts, we see the effect of the risk of the Fed cutting back on its purchases of U.S. Treasuries through its QE programs. From the beginning of May 2013, the yield on U.S. Treasuries rose in direct response to the likelihood that the Fed would begin tapering as early as September 2013, which was largely based on the perception of a strengthening U.S. economy. That probability peaked in early September, after which it became clearer that the Fed was less likely to act to taper its QE programs in September as the economy isn't recovering from being in microrecession as strongly as some data would indicate.

Through this period, both President Obama and the U.S. Treasury Secretary Jack Lew have made statements indicating that they would refuse to negotiate with congressional leaders to avoid a government shutdown or a default on the U.S. national debt, which they targeted to occur in mid-October 2013. The yields of U.S. Treasuries did not react meaningfully to their statements as we should expect if markets really believed that the risk of a U.S. default had increased.

Through this period, both President Obama and the U.S. Treasury Secretary Jack Lew have made statements indicating that they would refuse to negotiate with congressional leaders to avoid a government shutdown or a default on the U.S. national debt, which they targeted to occur in mid-October 2013. The yields of U.S. Treasuries did not react meaningfully to their statements as we should expect if markets really believed that the risk of a U.S. default had increased.

Their most recent statements came on Friday, 27 September 2013, once again emphasizing that President Obama would refuse to negotiate to avoid either a debt default or a partial shutdown of federal government operations. The yields for both the 2-Year and 10-Year U.S. Treasuries declined in response. If President Obama's claims had more credibility, yields on U.S. Treasuries would have risen in response.

But the spreads of the very lightly-traded CDS spreads for U.S. sovereign debt did, suddenly, within the last week - a jump so pronounced in the absence of any confirmation of a similar change in the yields of U.S. Treasuries that it is most likely attributable to a very small change the trading volume for it.

That kind of volatility is often a characteristic of low-volume trading activity in a market with low liquidity. It simply doesn't take very much money to create significant price changes.

It's kind of like how Intrade's prediction market for the 2012 U.S. Presidential election outcome was briefly manipulated to favor Mitt Romney following one of the presidential debates, only here, the manipulator of the market for U.S.' sovereign credit default swaps would appear to find President Obama's statements and policies to be credible.

The good news, if you can call it that, is that because of that fact, we know it wasn't the Russians, Iranians or Syrians. In this day and age, you have to take the good news where you can find it!

![Woman posed with stack of packages of $1 silver certificates at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, Washington, D.C. [between ca. 1950 and ca. 1969] Source - loc.gov/rr/business/money/paper.html](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgLuI_rEhkyjVyl-y5TaZa9f8hf9ZyMm8pwKI0L15k9suCFbE2x2C4I8DkwcKHSkcBTDqDjLrzbKW6F2XMIua45kKiETzeleIl1M3yWQ9zVhwVbKOVMiVDgct_XB4L7YGVSaxgOs6mkSwg/s320/a-money2_3b38767r-source-loc-gov.jpg)